When the Allied forces conquered Germany, they were able to liberate only some tens of thousands Jewish prisoners from the camps. Between 1945 and 1950, however, the former Third Reich was a temporary place of refuge for about 200,000 Shoah survivors. Besides the prisoners freed from the work and death camps, these were people who had fled from the Nazis to Russia, had fought in Eastern Europe with the partisans, or had in some other way managed to survive underground. Starting in the fall of 1945, the US military government set up special Displaced Persons (DP) camps for these people. For a short time, the US General Eisenhower had even considered allowing the Jews their own territory in Bavaria. David Ben-Gurion, who was traveling through occupied Germany in at that time, proposed this plan to Eisenhower. However, this did not result in a Bavarian Jewish state. Nevertheless, the Americans did generally allow the Shoah survivors the right of self-determination. The British, Russians, and French granted no such privilege. Supplies, too, were more plentiful in the American zone, and so about 85 percent of all Jewish DPs went to this zone, considering their residence in the camps as only temporary. The majority believed that their future would only be guaranteed in a country of their own, as they were convinced that „only Eretz Israel will succeed in absorbing and healing them, help them regain their national and human balance.“

But the state of Israel would not be established until 1948. For that reason, some Jews dreamed of a new life in the USA, Canada or Australia, but these countries were hardly welcoming and granted entry to only small numbers of immigrants. For example, the Institute of Jewish Affairs in New York City complained that, in the period from July 1947 to June 1950, the Australian authorities allowed just 4,745 Jewish DPs to enter the country, although the Australian Minister of Immigration, Arthur Calwell, had promised „to do everything possible to expedite the arrival in Australia of these unfortunate survivors of Dachau and Belsen and Buchenwald and Auschwitz.“

But throughout the whole post-war period the Australian Government’s aim was to strictly limit European Jewish immigration: The fear that anti-Semitism would rise was Calwell’s primary concern. Therefore, Jews, and Jews alone, had to declare their ethnic or religious origin on the immigration forms. Additionally a quota system was introduced which limited the number of Jews on any boat or plane to 25 percent.

Despite these restrictions, the Australian government eventually allowed thousands of Shoah survivors from the DP camps to come to Australia.

The first ship, the French liner Ville d’Amiens, with about 180 Jews on board, docked at Sydney harbor in November 26, 1946. Ultimately, Australia accepted about 17,000 Jewish refugees from the DP Camps and Communities in Europe; that was the second highest number of Shoah survivors, in relation to population size, after Israel. These Jewish „new Australians“ faced the problems of adjusting to a new language and culture and struggled with the psychological traumata of the Shoah. Despite these huge difficulties most of the immigrants found happiness in Australia and became loyal and thankful citizens.

One common reason – and certainly not the least important – for immigrating to such a remote place as Australia, was to get as far as possible from the scene of the catastrophe.

The story of the despairing survivors of the Shoah who spent years stuck in the middle of the land of the perpetrators, yearning for a new and safe homeland, and finally finished up living in Australia, has remained mostly untold until now – especially in Germany. The film-project „A new home down under – the migration of displaced persons to Australia“ is related through eight contemporary witnesses.

The 29 minute TV documentary „Destination: Down Under“ (German) was broadcasted (terrestrial, cable and via satellite) by the regional TV station Franken Fernsehen in February 2011.

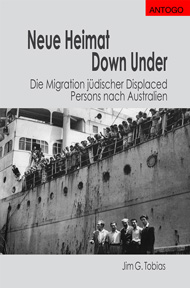

The book Neue Heimat Down Under. Die Migration jüdischer Displaced Persons nach Australien

The book Neue Heimat Down Under. Die Migration jüdischer Displaced Persons nach Australien

(German) has been released in 2014 incl. the TV documentary „Destination: Down Under“.